Mother of all Tomboys

artist Christina Schlesinger on Romaine Brooks

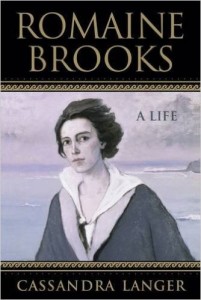

October 2 is D-day for Cassandra Langer’s new biography of Romaine Brooks (you can buy it here), for which I furnished translations. Readers will soon take a fresh look at the Thief of Souls.

Christina Schlesinger started incorporating Brooks into her self portraits in the mid-1990s. To find out why, I caught up with the East Hampton based artist and activist after a late September swim.

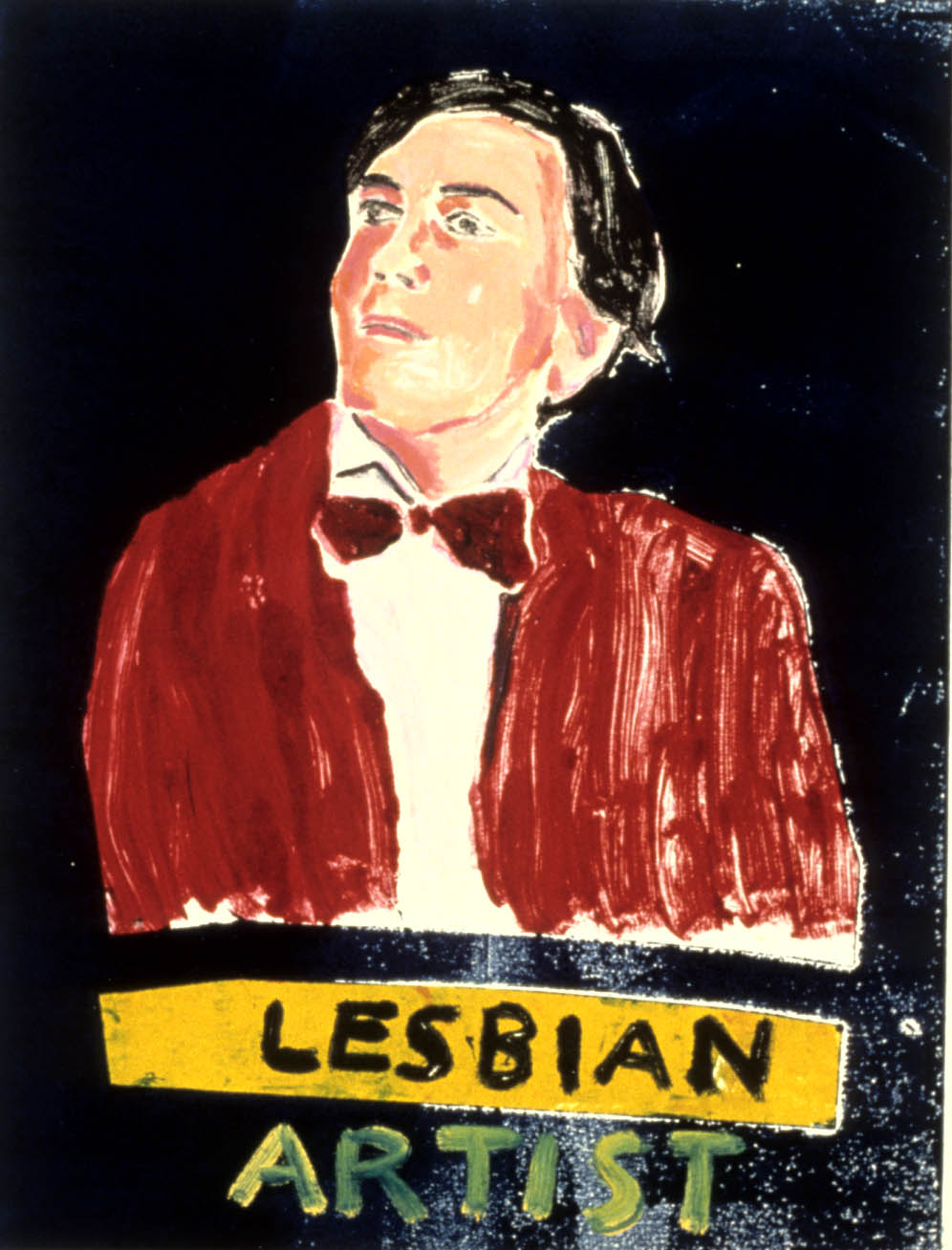

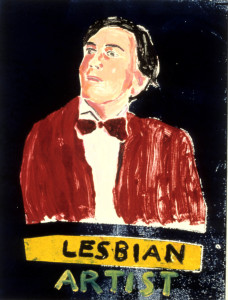

Suzanne Stroh: “Lesbian Artist” is a strong piece. Tell me about it.

Christina Schlesinger: It was based on a photograph I saw of Romaine Brooks. There she is in her smoking jacket wearing a bow tie with a kind of wild expression on her face. There’s so much spirit in her. In her gesture. It’s like my idea of the tomboy—defiant, intrepid, brave.

The photograph was black and white. Romaine’s own palette was famously subdued. Here, yours is bold.

I wanted her to stand out. Primary colors—red, yellow and Navy blue. The lesbian artist who’s out for a night on the town, ready to party, looking hot and jaunty. Making the scene.

Iconic really.

It’s a statement about being a lesbian artist. Romaine is the ultimate lesbian icon. She identified as a lesbian, she painted as a lesbian and she painted lesbians. I wanted to get across the idea of her as the model, the emblem, the forerunner.

“Romaine Brooks and Me” will be exhibited through mid October at New York’s Westbeth Gallery. It’s one in a series of portraits and self portraits. Have they ever been shown together?

As a matter of fact, no, they haven’t. I made several Romaine pieces, a total of about fifteen, several monoprints and other small paintings using images from Romaine Brooks. [Read more about the Peter Paintings here.] I painted them in my early 40s during a period of self-doubt.

In graduate school at Rutgers?

Around 1994. My thesis was on Romaine Brooks.

Why Brooks?

I just love her work. I read that first biography, Between Me and Life, and I was so intrigued to find that somebody was painting lesbians. People didn’t know – I didn’t know — about her work. I made a special trip to to DC to the National Portrait Gallery to see her work. I’ll never forget it.

She became an exemplar, a model. She was like an ancestress. A foremother. Somebody that I could look back to and draw inspiration from.

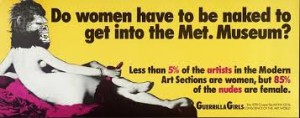

You know I’m a Guerilla Girl, right? Guerilla Girls take on the names of dead women artists. Mine is Romaine Brooks; I was the only lesbian at the time we founded the group. I identified with Romaine Brooks for a long time. So my “anonymous” Guerrilla Girl identity is Romaine Brooks.

You know I’m a Guerilla Girl, right? Guerilla Girls take on the names of dead women artists. Mine is Romaine Brooks; I was the only lesbian at the time we founded the group. I identified with Romaine Brooks for a long time. So my “anonymous” Guerrilla Girl identity is Romaine Brooks.

Wait, that’s anonymous?

[Laughs]

So how did Brooks get into your self portraits?

I took her on as somebody whose work I admired and just decided to riff on it. In one, I took the palette from the seaside self portrait of Romaine Brooks. The one on the cover of Sandy’s new book.

Romaine Brooks, “Au Bord de la mer (At the Edge of the Sea),” 1914. Oil on canvas, 41-3/8″ x 26-3/4″. Musée de la Coopération Franco-Américane, Blérancourt, France.

That’s the lesser known of the two. What do you like about it?

I like how melancholy and strong it is. There is a sadness and strength that I like. That’s what I tried to put in my own painting.

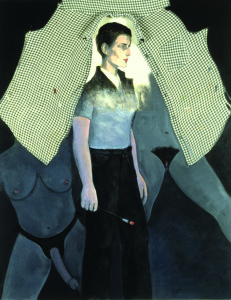

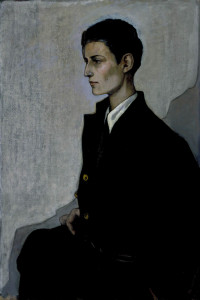

I liked the very androgynous women that she was painting. So I used Peter as Romaine even though she’s not really Romaine. It’s Peter, but it’s by Romaine. I like the androgynous quality of the Peter figure. The name even. Peter.

Let’s take a look at “Self Portrait as Romaine Brooks.” The central figure is an artist. Clothed. Dressed in black and grey, she stands in profile holding a paintbrush with a dab of red paint at the tip of the brush.

It’s a clitoris. Men paint with their penises, right?

She stands between two female nudes.

Either she’s dreaming about the two women having sex, or…. She’s being sexual in her own creativity.

Christina Schlesinger, “Self Portrait as Romaine Brooks,” 1994. Oil and fabric on canvas, 52″ x 40″.

We gaze at their torsos. One nude figure wears a realistic-looking strap-on dildo. The other has the same thick dark bush that you like to paint.

Yes, I guess that dates this work! Young lesbians now don’t have bushes. They shave. But I think it’s sexy.

Their torsos are all we get of this pair, since both heads are obscured by a black-and-white checked waistcoat. You cloaked or draped the painted image in the fabric. Tell me about that garment.

It was one of my flannel shirts — only the front shirt panels, with the flannel arms missing. I use a lot of my own clothes in my work.

I saw those in the Tomboys series you exhibited in 2014 at the Leslie-Lohman Museum. The show was called “All True Tomboys.” You write of your quest for “that bright and sturdy tomboy spirit.”

I found myself wondering, “When did I feel good? When did I feel confident?” That’s when I started the series. Whenever I can get that feeling inside of me, it’s so important.

Where do you find it these days?

Hopefully, I only need to look inside.

Who first called you a tomboy?

I always called myself a tomboy. I loved being a tomboy. It’s who I was. I had a younger brother, and there was another younger boy living next door, and I was the leader of our little gang. It was two little boys and me. We built a fort, played marbles, wore Davy Crockett hats, stole comic books from the corner drugstore, and did all these tomboy things together.

Of course my mother was always trying to put me in dresses. So there were constant fights over that. My mother (who’s 103 years old, by the way, and still totally with it) is a painter. She used to paint portraits. She had a Rollieflex and took pictures of her subjects. And me. So I have a lot of photographs of my being a tomboy. I used them as a source for my art. There are also some photos of me in dresses where I’m looking really squirmy. The emotion is totally different. You can see the conflict with my mother. Whereas when I was photographed as a tomboy, I was completely at ease and self-confident.

So back to the flannel shirt draped over the painting of Brooks and her clitoris. What’s its function?

It frames her. It is almost like a pair of wings, surrounding and protecting her. It is also a sign, the flannel signifying lesbian.

Unifying all the figures is the color red—rouging an aroused clit, the lips of a sensitive mouth, the erect nipples on a pair of compact breasts.

It is a circle. Your eye jumps from one little pink dot to another in a kind of circle. The colors pop out against the dark gray and black palette of the painting.

All true tomboys are defiant, confident in their bodies, intrepid, tender and brave.

Christina Schlesinger

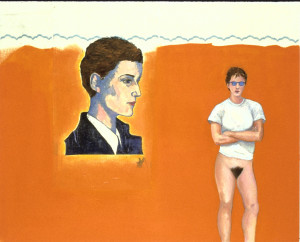

And then there’s “Romaine Brooks and Me,” a self portrait reproducing the Peter figure as a plinthless bust. Or maybe a poster child. What’s that pattern at the top?

The pattern is the blue scalloped edge of an actual bed sheet. Bed – sex!

There are two figures in the painting. The scale of the two figures is different. On the left you have a large profile of the Peter/Romaine; opposite and smaller stands the figure of a woman, arms crossed over a white T-shirt. She’s strong, lean, muscled. Fit. She stands confidently in mirrored blue shades with tousled hair and gazes straight at us. She’s cool. No hint that she’s an outsider. Except she’s nude from the waist down. It’s an unsettling effect similar to what I feel looking at the dildo paintings in the Tomboys series. I want to return her gaze but I can’t take my eyes off her crotch.

That’s me. The arms crossed in front—most of the tomboy paintings have that posture. Defiance and confidence.

Complete the sentence: “All true tomboys _________________.”

All true tomboys are defiant, confident in their bodies, intrepid, tender and brave.

What do you hope to learn from the new biography of Brooks?

Anything new that can illuminate her life will be very interesting. I’ve never really understood her drawings that well. I’m kind of curious about those.

I’m hungry for information. You know, “All True Tomboys” was exhibited in New York’s Gay and Lesbian Museum that hardly ever shows lesbians. I’m interested in writing something on lesbian sensibility and lesbian aesthetics. You have to begin with Romaine Brooks. Unless you go back to the Fontainebleau sisters.

Unknown artist, “Gabrielle d’Etrées et une de ses soeurs, duchesse de Villars” c. 1594. Oil on canvas, 37.7″ x 49.2″. Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

That naughty picture of Gabrielle d’Estrées and her sister? With like the Heat Miser and Snow Miser hairdos? Big in the 16th century I guess. I know that one. They’re playing in the bath. And I know just what they’re playing in the bath. Anonymous artist. Fontainebleau school.

So: lesbian aesthetics and the history of lesbian sensibility in Western art. Apart from antiquity. Would you include Courbet?

I suppose you could put Courbet in there, of course. And Toulouse-Lautrec. But those are men.

For lesbian aesthetics do you need a lesbian artist?

I think so. Certainly there are men who can appreciate lesbians and make art about them but they are really only observers, even if very gifted ones. A lesbian paints from her experience as a woman and a lover of women.

What about Gluck? British painter Hanna Gluckstein. Great biography by Diana Souhami. Gluck is Peter.

Gluck is Peter? I had no idea.

I’ve always wanted to see Gluck’s portrait of Romaine. The one she never finished, after Romaine quit sitting. What do you think it looked like?

I would be very intrigued to see Gluck’s portrait of Romaine. I understand that it was not finished because Romaine didn’t like it, which makes the story even more intriguing. What didn’t she like about it? Did Gluck see something in Romaine that Romaine didn’t want seen? Was there an issue of privacy? Of being invaded in some way? Maybe it was too revealing. Romaine’s self portraits have veiled qualities. She’s kind of masked and enigmatic. I see Romaine as a very private, almost hidden person. Maybe she was being revealed in a way she found to be uncomfortable.

Up to now, I’ve been completely entranced with the Peter figure. I was so attracted to this image. I had no idea of the back story. This is a whole new avenue for me to go down. This is more hidden history. You just want to keep filling it in. I’m totally inspired. Entranced.

Christina Schlesinger’s new work will hang in the group show “Figuring Abstraction.” It runs September 26-October 11 at Westbeth Gallery, 55 Bethune Street, New York. More about the show at www.westbeth.org

More about the artist at WWW.CHRISTINASCHLESINGER.COM.

All images copyright © Christina Schlesinger and reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. It is unlawful to reproduce or store these images on electronic media without the written permission of Christina Schlesinger.

[…] Suzanne’s interview with Christina HERE. More about the artist at […]

Bravo Christina for being a Gorilla Girl,… I wish I had been, I was so out of it, busy being a single mommy of three great kids teaching and struggling to get into my studio.We women artists owe you Gorillas a debt of gratitude.

Loved Suzanne’s interview with you.

Thanks for stopping by, Angela.

Hello Christine, this is a chance to talk with you. I hope I was your neighbor years ago in about 1974 in Venice. I have drawings that were thrown in the trash at that time of the Chagall mural. I have tried to contact you before to see if you want them. Please let me know. I’ve been saving them for you all these years. Hopefully you would like to have them